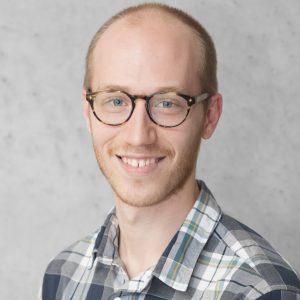

SAN Lab Graduate Student Brendan Cullen received a 2018 Graduate Research Fellowship (GRF) from the National Science Foundation. The prestigious GRF award will fully support Brendan’s doctoral studies for 3 of the next 5 years. Congratulations, Brendan!

Tips for Coaches and Consultants to Help Clients with Goals and Behavior Change

Our new piece in Consulting Psychology Journal approaches goals and behavior change from a coaching perspective. How can coaches and consultants help their clients set better goals and effectively change their behavior?

Dr. Berkman wrote a plain language summary on the Motivated Brain here.

Citation info:

Berkman, E.T. (2018). The neuroscience of goals and behavior change: Lessons learned for consulting psychology. Consulting Psychology Journal, 70, 28-44. [pdf]

New Article on Teen Risk Taking

Several folks from our group led by doctoral candidate Jessica Flannery have a new piece on teen risk taking over at The Conversation, “Teens aren’t just risk machines – there’s a method to their madness”.

You know the conventional wisdom: Adolescents are impulsive by nature, like bombs ready to go off at the most minor trigger. Parents feel they must cross their fingers and hope no one lights the fuse that will lead to an explosion. Adults often try restricting and monitoring teens’ behavior, in an effort to protect these seemingly unthinking riskseekers. That’s the tale told in the media, anyway.

Neuroscience evidence has seemed to bolster the case that adolescents are just wired to make bad decisions. Studies suggest that brain regions associated with self-control and long-term planning, such as the prefrontal cortex, are still developing. At the same time, adolescence is a time of increased activity in a brain region associated with reward, the ventral striatum. The story goes that these out-of-control teens are both extra sensitive to rewards and unable to rein in impulses – and thus naturally risky. They just can’t control themselves because their brains are unevenly developed.

As psychologists who focus on adolescents and their developing brains, we believe that teens have gotten an unfair rap. There are important developmental reasons adolescents act the way they do. They’re driven to explore their environments and learn everything they can about their surroundings. A teenager’s job, developmentally speaking, is to try out new behaviors and roles. Doing that sometimes involves risk – but not necessarily risk for its own sake.

Read the full piece here.

UPDATE (March 21, 2018): You can listen to Jessica discuss the piece on the Matt Townsend show here.

Bill Walton Visits SAN Lab

Former UCLA Bruin and Portland Blazer basketball star Bill Walton stopped by the lab for a quick scan of his brain for a segment on his ESPN show, Walton’s World. See below for some pics!

Quack Chat on New Year’s Resolutions by Dr. Berkman

Come hear Professor Berkman talk about evidence-based tips to help keep your New Year’s resolutions. He’ll present a #QuackChat at the Ax Billy Grill in the Downtown Athletic Club on Wednesday, December 13th, at 6pm.

http://around.uoregon.edu/content/neuroscientist-will-reveal-secret-making-resolutions-stick

Read Dr. Berkman’s New Take on Healthy Choice

Healthy choices are neither good or bad; only thinking makes them so

Serggod/Shutterstock.com

Elliot Berkman, University of Oregon

Doing healthy things can feel like a battle between the angel on one shoulder and the devil on the other. The devil impels me to order the bacon burger for lunch, but the angel nudges my hand toward the salad.

This dichotomy goes way back in Western thought. Plato likened the process of making such choices to the charioteer of the soul commanding two horses, one “noble” and the other wicked. This allegory echoes throughout history in various forms. Other ready examples include reason versus passion as described by the Greeks, the Judeo-Christian battle between sin and redemption, and Freud’s account of the psyche’s superego and id. Our intuitions about healthy behaviors are deeply shaped by this history. Plus, hard choices simply feel like we are being pulled in two directions.

Getting to the root causes of healthy behaviors is important to science because they are a big part of individual and public health. The leading causes of death in the United States – cancer, heart disease and respiratory illness, among others – are all caused at least in part by our behavior. As a society, we could reduce the onset of these afflictions by learning new ways to change our behavior.

Despite the intuition, health behaviors are not the result of a battle between two opposing forces. So what are they? My colleagues and I recently suggested that they are the same as any other choice. Instead of a battle between two forces, self-control of unhealthy impulses is more like a many-sided negotiation. Various features of each option in a choice get combined, then the total values of the options are compared. This is kind of a fancy version of a “compare the pros and cons” model.

Problems with the battle analogy

These days, psychologists refer to the dichotomy in Western thought as “dual-process” models of health behavior. Such models come in many varieties, but they share two notable features. First, they describe behavior as a winner-take-all battle between two opposing forces. There is no compromise. Whichever force is stronger dictates behavior.

Second, beyond being in opposition to one another, the forces are also inflected with a moral tone, with one being good and the other wicked. The devil impels you to do bad things, the angel advises toward virtuous ones. Psychologists call the warring parties impulse and control, or hot and cold processes.

Casting behavior in the stark terms of pros versus cons is intuitive but might not be accurate. After all, our minds contain many more than just two systems for making decisions. As Walt Whitman said, “I contain multitudes.”

Plus, people have many ways to choose healthy options that don’t involve a battle. Avoiding a temptation in the first place is effective. If I know that I have trouble not ordering the bacon burger, then I can choose to go to a restaurant that doesn’t have one on the menu.

Also effective is fighting fire with fire by getting excited about a healthy option. And being healthy doesn’t need to be moralized. Indulgence can be a good thing, such as when it serves as a reward. Some people even plan indulgence in advance to give themselves a break. In studying healthy choices, scientists have learned that they are more complex than we previously thought.

Advantages of thinking of many choices

Michaylovskiy/www.shutterstock.com, CC BY-SA

Let’s revisit the burger-vs.-salad example. Sure, the burger tastes good (a “hot” feature) and you know that the salad is healthy (a “cold” feature). But many other features could be relevant, too. Not all of them will fall clearly into the hot-cold dichotomy. The salad will seem more attractive if you want to impress the friends you’re with if you think they value health. Or maybe I think of myself as a “bacon person,” so I know ordering the burger with that topping will affirm that part of my self-concept.

The key point here is that people can have many reasons for making the healthy or unhealthy choice. A good psychological theory will be able to account for that diversity of motives.

Beyond being more realistic than hot-cold models, there are several ways that thinking of health as a choice can help us better understand it. Researchers working across a variety of disciplines have uncovered what they call “anomalies” in choice. These anomalies are quirks where choice differs – predictably – from what would be optimal. If health is a choice, then these anomalies apply to health, too.

One of my favorites is the decoy effect. There are cases where having a third option in a choice, even one that someone would never choose, can change behavior. Suppose I always prefer a burger to a moderately healthy salad. A restaurant owner could add a decoy choice to the menu, such as an Extremely Healthy SuperFood Salad, that would nudge me to choose the moderately healthy salad over the burger when I considered all three options. This behavior is anomalous – why would an option that I never choose influence my choice between two others? – but it is also useful in helping change health behaviors.

Another anomaly that can be useful for changing health behaviors is realizing that the value of something good is not constant. This is called the law of diminishing marginal utility. The value of something good depends on how much of that thing you’ve already consumed.

This is intuitive, but technically irrational. If I like M&M’s, eating the first one (going from 0 to 1 M&M’s) should feel just as good as eating my 104th one (going from 103 to 104 M&M’s). But we all know that is not the case. The deliciousness of things like M&M’s wears off as you keep eating them – their utility diminishes. In a clever series of studies, researchers found that merely imagining eating tasty treats before being served them reduced the amount people ate. Imagined eating, it seems, caused their utility to diminish.

Casting health behaviors as choice also helps clarify their neural underpinnings. The brain systems involved in simple choice are increasingly well-understood. The science has even progressed to the point that researchers can use computers to predict what people will choose and precisely how long it will take them in specific conditions. This improved understanding will eventually lead to more effective interventions for behavior change.

But wait – if healthy is just like any other choice, why does it feel like being pulled in two directions? We tend to moralize health behaviors in our society. Part of that feeling is probably related to the anticipated guilt of choosing the “bad” option.

Everett – Art/Shutterstock.com

And, morality aside, choice models show that people will feel torn when their preferences vacillate between options.

Just because there are two competing options doesn’t imply there are two competing systems. Feelings of conflict and indecision can arise even in a simple choice system such as the one described here.

![]() Remember that your health is not helpless amidst a battle between temptation and grace. It’s your choice, and science offers solutions to making a better one.

Remember that your health is not helpless amidst a battle between temptation and grace. It’s your choice, and science offers solutions to making a better one.

Elliot Berkman, Associate Professor, Psychology, University of Oregon

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

We are hiring!

The SAN Lab is pleased to announce that we’re hiring a full-time project coordinator to work on a new longitudinal fMRI study of eating behavior change! Applications are due at the end of August, and the start date is in early September.

You can read more and apply HERE.

Project Description

The study is a four-arm RCT testing the efficacy of a behavioral response training, a cognitive intervention, and a dissonance-based intervention to change cancer-relevant eating behavior against a non-food control training.

Position Description

The Project Coordinator works closely with Dr. Berkman to direct the design and implementation of the intervention. The Project Coordinator supervises and trains staff, including NTTF employees, coordinates and tracks recruitment and retention of subjects, runs assessment sessions including neuroimaging, conducts telephone interviews, manages and analyzes neuroimaging and behavioral data, acts as the liaison of the project to on- and off-campus organizations, and works closely with Dr. Berkman to achieve project goals. Ongoing interaction with the internal review board for human subjects protection is also expected.

Compensation is commensurate with experience.

Minimum Requirements

• BA degree in psychology, neuroscience, or biology.

• Experience with human subjects research studies, particularly clinical trials.

• Expertise in SPSS and MATLAB, R, and/or Python.

• Experience with team management.

Professional Competencies

• Excellent oral and written communications skills, highly detail oriented, organized, and efficient, and able to work independently while seeking supervision as necessary.

• Outstanding interpersonal skills and creative problem solving are also critical.

• Proficiency in Microsoft Word, Excel, and text messaging.

Preferred Qualifications

• MA degree in psychology, neuroscience, or biology.

• Experience with clinical participant recruitment.

• Experience conducting standardized clinical assessments.

• Neuroimaging acquisition and/or analysis experience, preferably fMRI.

• Experience with obese/overweight, early adversity samples and/or community populations, ideally in the context of a randomized controlled trial.

• Experience developing marketing and public relations strategies.

• Expertise in SPSS and MATLAB, R, and/or Python.

• Experience with team management.

The University of Oregon is proud to offer a robust benefits package to eligible employees, including health insurance, retirement plans and paid time off. For more information about benefits, visit http://hr.uoregon.edu/careers/about-benefits.

The University of Oregon is an equal opportunity, affirmative action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the ADA. The University encourages all qualified individuals to apply, and does not discriminate on the basis of any protected status, including veteran and disability status.

UO prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, national or ethnic origin, age, religion, marital status, disability, veteran status, sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression in all programs, activities and employment practices as required by Title IX, other applicable laws, and policies. Retaliation is prohibited by UO policy. Questions may be referred to the Title IX Coordinator, Office of Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity, or to the Office for Civil Rights. Contact information, related policies, and complaint procedures are listed on the statement of non-discrimination.

In compliance with federal law, the University of Oregon prepares an annual report on campus security and fire safety programs and services. The Annual Campus Security and Fire Safety Report is available online at http://police.uoregon.edu/annual-report.

Applied lessons from the neuroscience of goals and behavior change

Our latest paper, in Consulting Psychology Journal, summarizes some practical lessons about goals, behavior change, and self-regulation that we’ve learned from neuroscience research. Read more below!

Abstract

The ways that people set, pursue, and eventually succeed or fail in accomplishing their goals are central issues for consulting psychology. Goals and behavior change have long been the subject of empirical investigation in psychology, and have been adopted with enthusiasm by the cognitive and social neurosciences in the last few decades. Though relatively new, neuroscientific discoveries have substantially furthered the scientific understanding of goals and behavior change. This article reviews the emerging brain science on goals and behavior change, with particular emphasis on its relevance to consulting psychology. I begin by articulating a framework that parses behavior change into two dimensions, one motivational (the will) and the other cognitive (the way). A notable feature of complex behaviors is that they typically require both. Accordingly, I review neuroscience studies on cognitive factors, such as executive function, and motivational factors, such as reward learning and self-relevance, that contribute to goal attainment. Each section concludes with a summary of the practical lessons learned from neuroscience that are relevant to consulting psychology.

Citation info:

Berkman, E.T. (in press). The neuroscience of goals and behavior change: Lessons learned for consulting psychology. Consulting Psychology Journal. [pdf]

How can behavioral economics inform behavior change?

Our latest paper asks how behavioral economics – and its catalogue of “anomalies” – can inform the study of health behavior and behavior change.

Objective: Traditional models of health behaviour focus on the roles of cognitive, personality and social-cognitive constructs (e.g. executive function, grit, self-efficacy), and give less attention to the process by which these constructs interact in the moment that a health-relevant choice is made. Health psychology needs a process-focused account of how various factors are integrated to produce the decisions that determine health behaviour.

Design: I present an integrative value-based choice model of health behaviour, which characterises the mechanism by which a variety of factors come together to determine behaviour. This model imports knowledge from research on behavioural economics and neuroscience about how choices are made to the study of health behaviour, and uses that knowledge to generate novel predictions about how to change health behaviour. I describe anomalies in value-based choice that can be exploited for health promotion, and review neuroimaging evidence about the involvement of midline dopamine structures in tracking and integrating value-related information during choice. I highlight how this knowledge can bring insights to health psychology using illustrative case of healthy eating.

Conclusion: Value-based choice is a viable model for health behaviour and opens new avenues for mechanism-focused intervention.

Citation Info: Berkman, E.T. (in press). Value-based choice: An integrative, neuroscience-informed model of health goals. Psychology & Health. [pdf]

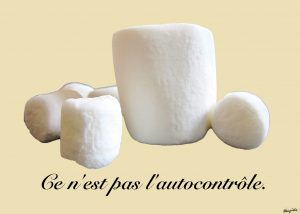

Is self-control just choice?

This is not self-control

Our new paper at Current Directions in Psychological Science asks whether self-control is “special,” or whether it is just like any other choice. We present a model for understanding and modeling self-control as value-based choice, and discuss the advantages that emerge from this approach. The most significant implication: extensive knowledge about how value-based choice works, including its various quirks and biases, can be brought to bear on the questions of why self-control sometimes fluctuates over time and how it might be improved.

Citation info:

Berkman, E.T., Hutcherson, C.A., *Livingston, J.L., *Kahn, L.E., & Inzlicht, M. (in press). Self-control as value-based choice. Current Directions in Psychological Science. [pdf]